New Voices In Old Rooms

By Madeline Zelazo ’22

The Porter-Phelps-Huntington Foundation and the UMass Amherst Libraries are working together to support ongoing research and outreach efforts. In 2021, the foundation moved its extensive archive, the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers, to the Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center at the Libraries to facilitate the research of UMass graduate students and faculty actively uncovering the diverse stories the site holds, such as its ties to the Atlantic slave trade and the displacement of native Nonotuck peoples.

When the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Museum in Hadley, Mass., opened in 1949, visitors learned about six generations of the family that lived there while strolling through rooms of imported furnishings and other decorative examples of refined taste. The original experience was curated by James Lincoln Huntington, who opened the museum, actively shaped its interpretation, and, until his death in 1968, led most tours of the house himself.

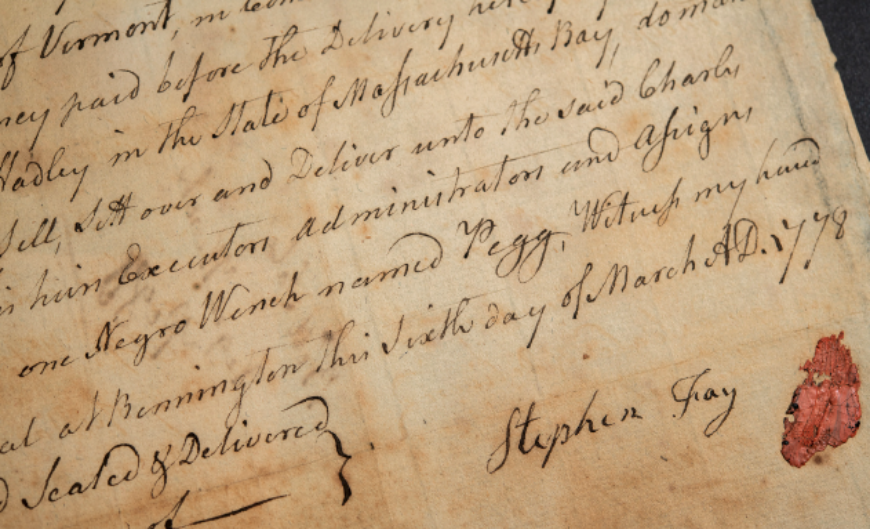

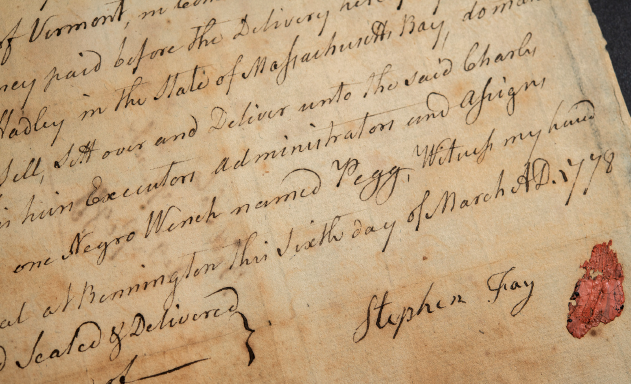

Seven decades later, visitors to the museum now hear stories that encompass the lives of many people who lived and worked on the farm known as “Forty Acres”: free and enslaved Black and Indigenous people, and the Porter-Phelps-Huntington women who kept the family farm running for over 200 years, some of whom were active abolitionists. This retelling is thanks to decades of work by the Porter-Phelps-Huntington family, the Foundation, the Museum, and UMass Amherst students and faculty working to help reinterpret the site through its extensive collection—thousands of letters written between scores of relatives and hundreds of objects original to the farm and home.

To make the house conform to his vision of genteel domesticity, James Lincoln Huntington transformed a summer home into a Colonial showplace. As he restored the property, he erased other parts of his family’s past. Victorian era furniture was tucked away, and the places where work was done—the barn and the outbuildings—were sold or torn down. The house that remained emphasized his ancestors’ gentility, destroying evidence of the complex labor and social relationships that linked the household at Forty Acres to the community and region.

The reinterpretation of the historic house museum is the result of a unique partnership forged between the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Foundation and the UMass Amherst Libraries; the two institutions formally pledged to work together to support ongoing research and outreach efforts. In 2021, the foundation moved its extensive archive, the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers, to the Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center (SCUA) to facilitate, among other objectives, the work of UMass graduate students and faculty researchers actively uncovering the diverse stories the site holds, such as its ties to the Atlantic slave trade and the displacement of native Nonotuck peoples.

“We knew the papers needed to be in a place where people could continue to work with them. They had to stay accessible,” says Karen Sanchez-Eppler, head of the board of directors of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Foundation. “Collecting regional history is a priority for the research center, and the campus’s commitment to social justice resonated with the family. It’s also a rich collection for understanding agricultural history, so it fits with UMass in many ways.”

The papers had previously been on deposit at Amherst College and are now permanently part of UMass Amherst’s collections. Because of its timespan, the collection has been extremely valuable in enabling scholars to think about patterns across large demographic swaths. Another motive for the move, and one reason the collection is so distinctive, is because it is continuously expanding. “It keeps growing and changing as family members continue to donate more papers,” Sanchez-Eppler says.

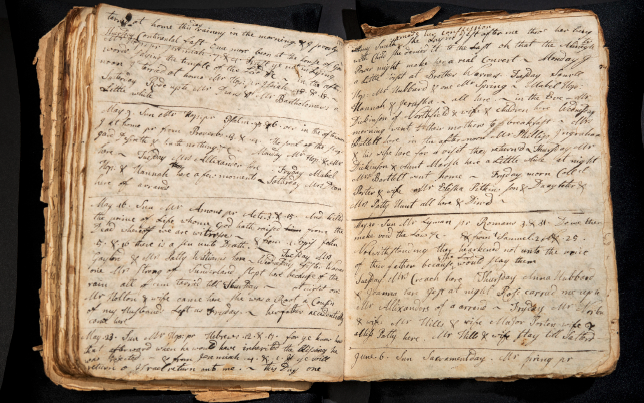

The meticulously kept records and documents provide a wealth of original source material for researchers. One item in particular, Elizabeth Porter Phelps’s extensive diary covering all facets of daily life, is considered to be one of the most important documents of the time period for understanding American culture, says Joshua dos Reis ’23, a UMass student in public history and the museum’s summer tour guide. “Not just by the museum,” he adds, “but by the historical community at large.”

UMass’s connections with the collection stretch back to the late 1980s when then-student Kari Harmon (née Federer) ’87 organized, described, and processed the family papers for her senior project. Harmon’s work resulted in the original guide to the collection’s contents and arrangement.

“In the 1990s, the museum undertook its first reinterpretation initiative, which wanted to think about broader stories the site could tell, and it really responded to the flourishing of women’s history,” says UMass Amherst history professor Marla Miller, who guides graduate students’ current work in the collection. “One of the outcomes was that the site shifted its focus to the women’s and labor history stories, so the tour was about the family who lived there, and also about the women who lived and worked there, and also the women and men who were enslaved there.”

In 2002, during a family reunion celebrating the 250th anniversary of the estate, foundation board members were met with pleas from the family to continue studying the collection. “My sense is that the family had a sense of their own history from the get-go. They saved everything,” says Susan Lisk, the executive director of the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Foundation. “The museum, from the beginning, was an archive, and James Lincoln Huntington always understood that was a strength.”

Beyond paper records, the museum’s weathered beams and floorboards have preserved a 270-year-long physical history of dairy farmers, laborers, slaves, indentured servants, seamstresses, Indigenous people, and Hadley elite. The Porter-Phelps-Huntington Museum is a rambling house with many additions, all filled with mostly original furnishings. It’s a shining local example of early settlement and significant architectural nonconformity.

The estate’s first sections were constructed in 1752 and then continuously owned, improved, and expanded by six generations of a Hadley “River God” family—a local lineage that prospered from trade along the Connecticut River. The main house and the surrounding estate operated as a farm and comfortable summer home for nearly two centuries before being converted into a museum by its last family occupant.

Professor Marla Miller works directly with students on the retelling of the museum’s story through the archives. Miller first became involved in the project while researching her 2019 book Entangled Lives, an examination of the Anglo, African, and Native American women who lived in Hadley during the town’s transformation following the Revolutionary War. In the wake of racial reckoning following the murder of George Floyd, “the museum wanted to do more, to surface even more diverse stories,” says Miller.

Professor Marla Miller works directly with students on the retelling of the museum’s story through the archives. Miller first became involved in the project while researching her 2019 book Entangled Lives, an examination of the Anglo, African, and Native American women who lived in Hadley during the town’s transformation following the Revolutionary War. In the wake of racial reckoning following the murder of George Floyd, “the museum wanted to do more, to surface even more diverse stories,” says Miller.

UMass public history graduate students have been working for two years on grant-funded projects focused on the reinterpretation of the site: to rewrite the National Register of Historic Places nomination; to uncover the twentieth-century rural Hadley Black community; and to redesign the museum’s tour in a way that encompasses the lives of all the people who lived and worked there.

Students have undertaken research to understand the ways in which people and communities articulate their understanding of their own history. Miller explained that, for instance, a visitor might look at the mahogany tea table and appreciate the artistry in it and the skill of the carver, because it’s a beautiful thing that this wealthy family could afford to purchase. “Now we think about what it meant to consume mahogany in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries,” says Miller, “because mahogany, like many things, was dependent on a large, enslaved workforce.”

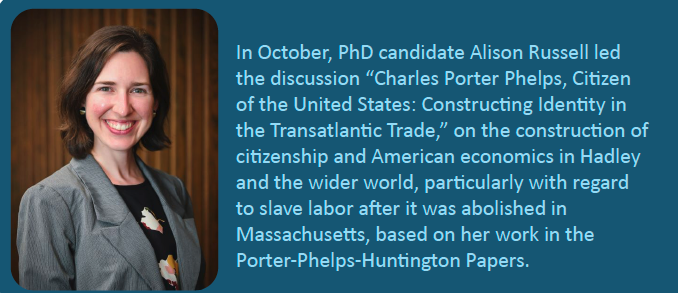

Graduate student Alison Russell ’26PhD has worked to uncover the family’s ties to the Atlantic slave trade. In her research, she studied a box of receipts originally found in the attic of the barn at the museum that document Charles Porter Phelps’s involvement in and profit from Cuban sugar imports that he resold in a multitude of places, including Europe. “He made connections in Denmark and Russia, and there are these letters from Saint Petersburg and a city in Russia called Archangel. It is amazing what connects with Hadley,” says Russell.

Graduate student Brian Whetstone ’25PhD is updating the museum’s original successful 1973 National Register of Historic Places nomination, to better encapsulate its historical significance. “I like to say that nominations in those days were kind of like the Wild West, like you could kind of just say whatever or do whatever. Their standards hadn’t really been established for this practice yet,” Whetstone explains, adding that only 3 percent of nominations are ever updated to represent new history.

The original nomination only mentioned early settlement and architecture as criteria, glossing over the agricultural importance of the site and much of its other history. “Our task was to both literally and physically expand the nomination as well as tie in stories that the original nomination had overlooked,” says Whetstone.

In his research, Whetstone studied how James Lincoln Huntington manipulated the site by removing farm structures no longer in use to tell a story of what he considered to be significant about the site. “He was interested in a romanticized idea about Colonial life where everyone was bred in dignity and refinement and they all lived genteel lives,” says Whetstone.

“Meanwhile, they had enslaved laborers at the house that were making that possible.”